Associate Professor Enrico Della Gaspera (left) and Dr Joel van Embden. Photos: RMIT University

Associate Professor Enrico Della Gaspera (left) and Dr Joel van Embden. Photos: RMIT UniversityAn international team of scientists is developing an inkable nanomaterial that they say could one day become a spray-on electronic component for ultra-thin, lightweight and bendable displays and devices.

RMIT University’s Associate Professor Enrico Della Gaspera and Dr Joel van Embden led a team of global experts to review production strategies, capabilities and potential applications of zinc oxide nanocrystals in the journal

Chemical Reviews.

Professor Silvia Gross from the

University of Padova in Italy and Associate Professor Kevin Kittilstved from the

University of Massachusetts Amherst in the USA are co-authors. Professor Della Gaspera said: “Progress in nanotechnology has enabled us to greatly improve and adapt the properties and performances of zinc oxide by making it super small, and with well-defined features.”

Dr van Embden added: “Tiny and versatile particles of zinc oxide can now be prepared with exceptional control of their size, shape and chemical composition at the nanoscale. This all leads to precise control of the resulting properties for countless applications in optics, electronics, energy, sensing technologies and even microbial decontamination.”

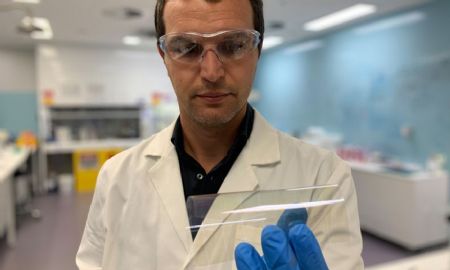

The zinc oxide nanocrystals can be formulated into ink and deposited as an ultra-thin coating. The process is like ink-jet printing or airbrush painting, but the coating is hundreds to thousands of times thinner than a conventional paint layer.

Professor Della Gaspera said: “These coatings can be made highly transparent to visible light, yet also highly electrically conductive — two fundamental characteristics needed for making touchscreen displays.”

The team said the nanocrystals can also be deposited at low temperature, allowing coatings on flexible substrates, such as plastic, that are resilient to flexing and bending. They are ready to work with industry to explore potential applications using their techniques to make these nanomaterial coatings.

Zinc is an abundant element in the Earth’s crust and more abundant than many other technologically relevant metals, including tin, nickel, lead, tungsten, copper and chromium. Dr van Embden added: “Zinc is cheap and widely used by various industries already, with global annual production in the millions of tonnes.”

Zinc oxide is an extensively studied material, with initial scientific studies being conducted from the beginning of the 20th century. Della Gaspera continued: “Zinc oxide gained a lot of interest in the 1970s and 1980s due to progress in the semiconductor industry, and with the advent of nanotechnology and advancement in both syntheses and analysis techniques, zinc oxide has rapidly risen as one of the most important materials of this century.”

Zinc oxide is also safe, biocompatible and found already in products such as sunscreens and cosmetics. Potential applications, other than bendable electronics, that could use zinc oxide nanocrystals include: self-cleaning coatings; antibacterial and antifungal agents; sensors to detect ultraviolet radiation; electronic components in solar cells and light emitting devices (LED); transistors, which are miniature components that control electrical signals and are the foundation of modern electronics; and sensors that could be used to detect harmful gases for residential, industrial and environmental applications.

According to the team, zinc oxide nanocrystals could be incorporated into many components of future technologies including mobile phones and computers, thanks to its versatility and recent advances in nanotechnology.

Professor Della Gaspera explained: “Scaling up the team’s approach from the lab to an industrial setting would require working with the right partners. Scalability is a challenge for all types of nanomaterials — zinc oxide included. Being able to recreate the same conditions that we achieve in the laboratory, but with much larger reactions, requires both adapting the type of chemistry used and engineering innovations in the reaction set up.”

In addition to these scalability challenges, the team needs to address the shortfall in electrical conductivity that nanocrystal coatings have when compared to industrial benchmarks, which rely on more complex physical depositions. The intrinsic structure of the nanocrystal coatings, which enables more flexibility, limits the ability of the coating to conduct electricity efficiently.

Professor Della Gaspera concluded: “We and other scientists around the world are working towards addressing these challenges and good progress is being made. I am confident that, with the right partnership, these challenges can be solved.”