Cranfield University

Cranfield University is a collaborative partner in an international project which has just launched a custom-designed 3-D metal printer powered by lasers to the International Space Station (ISS). Scientists believe that in the future, the ability to 3-D print metal parts on board the ISS would allow for the speedy replacement of components or the manufacturing of new ones. This would avoid the costly and time-consuming current approach of transporting physical parts into space.

3-D printers fuelled by high-powered lasers have never been tested in a space environment before, and scientists will be examining data from this test to understand how the process and the metal is affected by the microgravity environment.

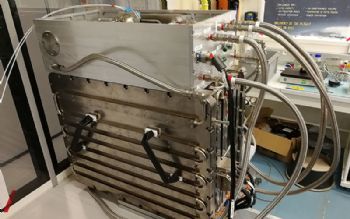

The 3-D printer was sent to the ISS as part of the payload aboard the Cygnus NG-20 mission which recently launched from Cape Canaveral in the USA. Resembling a metal box and weighing 300kg, it was transported in parts to be reassembled on board by astronauts.

Academics at Cranfield University were involved in designing the 3-D printer’s melting process and hardware, as well as its laser source, delivery optics, feedstock storage and feeding system. Manufacturing experts needed to take into account the need to avoid risk factors such as heat transfer. Another challenge was the low power availability, which required an efficient process in order to melt metals.

Dr Wojciech Suder, senior lecturer in laser processing and AM in Cranfield University’s Welding and Additive Manufacturing Centre, led on the design for the 3-D printer. He said: “We have measured the effect of gravity on liquids in space before. But we have not done this when 3-D printing components from liquid metal because of the high temperatures involved. Our task was to design a 3-D printer that can be thermally neutral, and cannot emit heat or radiation onto the ISS either.

“This meant it had to meet lots of requirements, in addition to being fully autonomous. It was quite a challenge, but one we successfully completed. Now it is a case of waiting for the samples to return and examining them. The purpose is to see the effect of microgravity on 3-D metal printing. If we can understand this more, we can find out how to best use this technology in space in the future.”

Andrew Kuh, exploration technology manager at the

UK Space Agency, said: “Developing efficient technologies that reduce our reliance on the costly and time-consuming transfer of materials from Earth is crucial to allow us to travel further into space for longer. AM in space is notoriously challenging, owing to the energy and materials required, but this innovative concept could make a huge difference to our ability to maintain spacecraft. Cranfield University’s contribution demonstrates how important UK skills and expertise are to global space exploration. We look forward to following the next steps of this fascinating technology.”

The Metal3D five-year project was led by

Airbus Defence and Space, working in partnership with Cranfield University, as well as

AddUp and

Highftech, and was commissioned by the

European Space Agency (ESA).